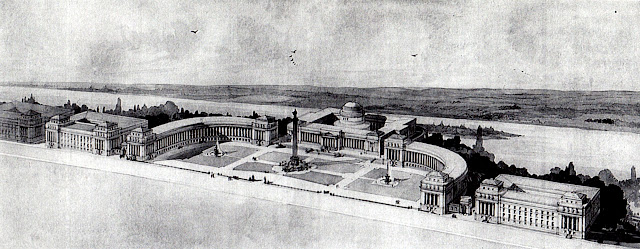

The development of a 'Mile of History' on Sussex Drive was the primary action item listed in the conclusions of the National Capital Commisson's landmark study of 1961. The mile turned out be a rocky road. Troubled by false starts, Government cancellations, fires and demolitions that were chasing ahead of the NCC's plans. One could say that while it has been underway for more than 50 years it's still work in progress. (Drawing: The 'after' picture, Sussex decked out in her Confederation-era dress - Preserving Our Heritage, NCC April 1961)

The Mile of Living History was 'given the official promise of realization with cabinet approval' on August 10, 1961, just four months after the release of the NCC's 'Preserving Our Heritage' report regarding the acquisition and restoration of historic buildings in the National Capital Region. An $8 million package of property purchases and construction costs, it had been elevated to the status of the Government of Canada's official Centennial Project for the City of Ottawa. (Ottawa Journal, August 10, 1961)

The clutter of Sussex Street's signage, fire escapes, and overhead wiring were particular bugbears to the NCC which labeled them as tatty, downmarket - a degradation of the historic buildings' dignity. The photo is also a reminder that Sussex was just half a street thanks to the Borden Government's cancellation of the defeated Laurier Government's 1906-07 grand plan for the Exchequer Court complex which had swept away all of the buildings on the west side.

Sneaking ahead to the final outcome of this story - all of the offending elements had been successfully expunged by the early 1970s. Of interest is the three-story brick structure with a tiny mansard roof and narrow window openings, the first new building to be constructed after the Mile of History was underway, replacing the Jules Patry wholesale warehouse that had left Sussex for the City Centre in 1963. Designed by Rosen, Caruso, Vecsei Architects of Montreal, it was an early effort at historicized modernism which has since been more heavily historicized with a more quaintly ornamented storefront.

Back to the beginning - in conjunction with the NCC's Advisory Committee on History in 1960 the restoration architect Peter John Stokes was retained. Through his elegant restorations at Niagara-on-the-Lake Stokes had established a reputation for historic sensitivity. He was asked to prepare specifications for the restoration of Sussex Street which 'when restored would have all the exterior finish completed in immaculate detail, to resemble the Confederation period. Store signs, windows, doors and awnings would be made to conform to those which were known to have previously existed.' The buildings X'ed out in this street elevation actually refer to later events in another block. (Preserving Our Heritage, NCC 1961)

The concept for a Mile of History was in large part sparked by the destruction of this handsome stone building at Sussex and Bruyere Streets, Thomas Goulden's Hotel (1852-1860). Judged to be one of the finest buildings on the street, its demolition was opposed by the Ottawa Historical Society which appealed to the City of Ottawa to save it, and a personal intervention by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. It was a great loss but it provided the impetus for some form of government action on the Mile of History. (Photo: LAC-e010934805)

Despite these protests, in December 1959 the fight was lost and the demolition proceeded the following summer for a gas station. Nonetheless it had a galvanic effect on the NCC, which had just been given the mandate to administer the conservation and restoration of historic buildings. (Photo: City Archives AN-004606)

Shortly after the ambitious report had been adopted and approved by the Government of Canada and just before the NCC could move to expropriate the buildings, one of Sussex's key blocks was significantly diminished when the Hotel du Canada and the Bishop's Block at the corner of St.Patrick Street were heavily damaged by a fire, and were taken down. (Photo: Michael Newton, Lower Town Ottawa, NCC 1980)

On the other end of the block at Murray Street the Laurendau Block-Valin Apartments met a similar fate, in the same year. By the time that the NCC acquired it the building was a burned shell, and their first action was to demolish it. (Photo: Michael Newton, Lower Town Ottawa, NCC 1980)

This was the St. Patrick-Murray Street block in its entirety although it was misidentified as Murray-to-Clarence in the 1961 report. Cost-recovery for the purchase and restoration would be amortized through office space rentals 'within a surprisingly short period'. It noted that 'Areas in other cities that have been preserved in this fashion have become a mecca for discriminating tenants, and it is not unrealistic to suggest that space in this area might become among the most sought after in Ottawa.' That prophesy has not come to pass, and during the ensuing decades commercial tenanting has been problematic.

Despite the availability of Peter Stokes' drawings and historic photographs, the NCC has not rebuilt the missing ends of the St. Patrick-Murray block, although it has never been hesitant about improving on history. (Photo: Michael Newton, Lower Town Ottawa, NCC 1980)

Five of the buildings on Sussex Drive are now facsimile reproductions of the original ones. This is a practice perfected by the NCC for reasons of efficiency and marketability, a technique that is not entirely embraced by the heritage industry.

Does Facadism always equal Disneyfication? It's the least best option for historic building restoration, but it's too late to ask. The National Capital Commission was proud of its work. (Photo: NCC Annual Reports)

In the four blocks beyond St. Patrick Street (top half of the 1961 report's drawing above) given the presence of three major institutional buildings there was no need to demolish and recreate - with the Notre Dame Church, Academy de la Salle, and the Grey Nuns/Sisters of Charity Convent in safe hands. This left only the Bruyere-to-St. Andrew section of Sussex, the site of Goulden's Hotel, to be dealt with. Which the NCC did with some enthusiasm, as it soon expropriated the gas station property, demolished the building, and built a small parking lot buffered by landscaping. In Peter John Stokes' concept plan this block was suggested for a new office building.

News of the Government of Canada's surprise announcement to expropriate the northern half of Sussex from Cathcart to King Edward was buried by their decision one month later (April 12, 1962) to seize five times as much land on Lebreton Flats. The Sussex expropriation of 32 acres containing 400 households came as 'a bit of a bombshell' during Ontario Municipal Board Hearings into a new medical-dental building proposed for the area. The NCC plan would ease all trace of Mactaggart, Redpath, and Baird Streets, and the former CPR railway yards. This tract of land was to be used for a variety of purposes, including new government buildings, the approaches to the proposed Macdonald Cartier Bridge, redevelopment of the 'Mile of History' running from St. Patrick Street to City Hall, and a further addition to the Rideau River shoreline park. (Ottawa Journal, March 14, 1962)

It was unclear how an extended Mile of History could possibly fit into the plans for a new roadway and government buildings, which required the removal of vast amounts of earth to create the interchange between Sussex and the Macdonald Cartier Bridge. (Ottawa Journal, August 24, 1963)

After all of the historic buildings north of Boteler Street had been cleared away the Mile of History was effectively terminated at the bend in Sussex Drive. (GeoOttawa, 1965)

Any possibility that the Mile of History that might have lead to the gates of Rideau Hall was permanently halted by this beast, the Lester B. Pearson Building, headquarters of the then Department of External Affairs (Webb Zerafa Menkes and Housden Architects, 1969). The architects defended their design as being extremely sensitive to its setting, but the External Affairs building was excoriated for being a hostile bunker. While it's mellowed somewhat with age it's hard to believe that its designers had ever visited the site. (Photos: Ottawa Journal, April 28, 1973, OFART-Old Foreign Affairs Retired Technicians)

By 1965 the Pearson Government's hardened stance on Sussex Drive had softened, a little. In his article ‘Old Street With a New Face’, architect Stig Harvor of Balharrie Helmer Associates summed up the change of heart. ’The austerity program of 1963 shelved plans of converting the building interiors into rentable, modern office space. The only work undertaken to date has been the exterior facelift. But what a visual change this facelift has produced! The buildings have regained, and one suspects, often surpassed, their old charm. They now form the only comprehensive attempt in Ottawa - and perhaps in Canada - to create a ‘streetscape’ where building materials, facades, colors, store fronts and signs are looked upon as a total composition rather than a composite of unrelated parts. We have the example of Sussex Drive as a dramatic illustration of the big effects which can be achieved with small means. Under the expert architectural eye eye of John Leaning, the National Capital Commission has spent about $80,000 to give Sussex Drive a colourful new appearance. - ‘Old Street With a New Face’ by Stig Harvor, Ottawa Journal, May 28, 1965. For about 1% of its original estimated cost the NCC had given the street a cheap and cheerful makeover. (Photo: NCC Annual Report, 1968)![]()

By the early 1970s the Mile of History project was in the ascendancy at the NCC. Work was hastened when one of the commercial buildings between George and York was destroyed by fire. The hole needed to be filled and while they were at it, the little building next door containing the Rose Cafe and La Hacienda could be improved upon. (Photo: City Archives)

It provided the first opportunity to put the NCC's new approach demolishing the existing buildings they deemed to be too 'structurally unsound', build facsimile historic facades attached to modern buildings that would serve another purpose - in this case commercial units at grade and loft apartments above. They would go on to do this to the Castor Hotel, and the Hotel du Canada/Laurendau Block.

Sometimes the buildings could be returned to a more 'appropriate' period. The 1870s facade of the Riel-McDougal blocks had been altered in the early 1900s by a fourth floor addition. (Photo: NCC Annual Report, 1974)

When it came time to rehabilitate the building for flats and new stores the top floor was removed and replaced by a highly conjectural attic story. A hybrid of this methodology was followed in the next block for the adaptive re-use of the Institut Jeanne d'Arc. (Photo: NCC Annual Report, 1980)

This philosophy has been the driving principle to architectural restoration on Sussex Drive since 1961: 'Sussex Street, restored to Confederation days, building facades renovated, advertising signs removed, sidewalk widened, trees planted, building signs lettered in period script.'

541 Sussex had been condemned and promised a new life once before, although nothing more came from these plans. ’FOR USE AS A MUSEUM - 'The old Custom House at Sussex and George will not now go under the wrecker’s hammer, Works Minister Winters announced Thursday [December 15, 1955]. Instead it will be turned over to the Historic Sites and Monuments Board for use as a museum.’ (Photo: JRAIC, 1955)

While it was initially the first priority restoration of the building was deferred for decades and it had make do with one of the NCC's interim inexpensive fix-ups, painting stripes on the blind attic story. (Photo: NCC Library)

Its many chimneys are still missing, but a standing seam metal roof, eaves with brackets, and an eyebrow dormer window have finally been returned to the former GGFG Militia Barracks, British/Clarendon Hotel, Geological Survey of Canada, Department of Mines, RCAF Dental Clinic, etc.

Peter Stokes' 1961 plan included an early concept for a chain of landscaped courtyards and parking areas behind the Sussex Street buildings, starting on George Street at the right and flowing through the Murray on the left.

The NCC acquired additional properties at the rear to accomplish this. (Photo: NCC Library)

They were used as surface parking for many years. To hide the lot the National Capital Commission built a stone screening wall with two arched openings along George Street in 1965. I can recall Rolf Latte, the Commission's sharp-tongued Information and Heritage Officer crowing that when the City of Ottawa first established its Heritage Buildings Reference List in 1979 they had been fooled by the NCC's new wall and included it in their list of historic structures.

The wall had to come down for the Clarendon Court.

Through fits and starts the Mile of History has reflected the rise and fall of the National Capital Commission's budgets and political influence. Lauding the plans for the Mile of History in its editorial of June 19, 1961 the Ottawa Journal had said 'It is satisfying the learn that a detailed study has been prepared for part of the street between the Basilica and York Street showing how buildings may be restored, "woven into the historic fabric", to use the NCC's good phrase. ...These plans must not be considered as merely visionary and impractical. The NCC keeps its mind on the main task in bringing forward new ideas. We need more, not fewer plans. We need daring and imaginative concepts which will make Ottawa a city of culture, a place which nourishes humane values, as well as a city of expressways and open spaces.'

The Mile of Living History was 'given the official promise of realization with cabinet approval' on August 10, 1961, just four months after the release of the NCC's 'Preserving Our Heritage' report regarding the acquisition and restoration of historic buildings in the National Capital Region. An $8 million package of property purchases and construction costs, it had been elevated to the status of the Government of Canada's official Centennial Project for the City of Ottawa. (Ottawa Journal, August 10, 1961)

By the end of 1961 the City of Ottawa) or at least Mayor Charlotte Whiten) had become an enthusiastic support. She charged that “fly-by-night companies” were trying to capitalize and the Federal Government’s plans for Sussex. She said that it was “deplorable… scandalous… unpatriotic that two or three avaricious people are speculating in land”, and urged the City to endorse a companion project in the Byward Market by approving a temporary zoning by-law that would freeze development in this part of Lowertown. ‘The city hopes to “preserve, reconstruct, and renovate” the market area in an extension of the Mile of History project.’ The Mayor’s efforts were ultimately stymied by the Dalhousie District Businessmen’s Association and the Ward’s two Aldermen. (Ottawa Journal, December 5, 1961) ![]()

Visited by successive fires, historic facades hidden under plain fronts, and dominated by mostly gritty businesses, the Sussex Street of 1959, as photographed from the roof of the Connaught Building, gave little hint of its role as Ottawa one of most important commercial thoroughfares. (Photo: LAC, Ted Grant Collection)

The clutter of Sussex Street's signage, fire escapes, and overhead wiring were particular bugbears to the NCC which labeled them as tatty, downmarket - a degradation of the historic buildings' dignity. The photo is also a reminder that Sussex was just half a street thanks to the Borden Government's cancellation of the defeated Laurier Government's 1906-07 grand plan for the Exchequer Court complex which had swept away all of the buildings on the west side.

In 1963 Sussex was the scene of another political axe-wielding when ex-P.M. Diefenbaker’s pet projects (like the Mile of History') were nixed by the newly-elected Liberal Government . ’For Centennial - No Plans To Dress Up Sussex - 'Any “mile of history” on Sussex Drive in conjunction with the 1967 centennial “would be a mile of future history,” Privy Council President Lamontagne said at the closing press conference on the National Conference on the Centennial, when asked about the development of Sussex. “If there was to be a mile of history erected there,” he replied, “it would be a mile of future history, since we have demolished most of the historic buildings along there.” He added that no plans were being entertained to do anything else to Sussex.’ (Ottawa Journal, October 17, 1963)

After more than a year in office the Pearson Government remained firm. ’Mile Of History Stalled - 'Federal plans for restoration of two historic areas of Ottawa have been consigned to limbo. State Secretary Lamontagne said that development of both the Mile of History on Sussex Drive and the pioneer settlement on Richmond Landing is being delayed. They had been conceived and pushed by former Prime Minister Diefenbaker as part of Ottawa’s centennial planning. ‘ Lamontagne added that no detailed plans had been worked out because the NCC had to devote its time and money to other projects of higher priority. Buildings on Sussex would have their outsides painted and cleaned, but no structural changes would be made. The ‘pioneer settlement’ and park at Richmond’s Landing would have to wait until the future development of Lebreton Flats. (Ottawa Journal, June 4, 1964) Sneaking ahead to the final outcome of this story - all of the offending elements had been successfully expunged by the early 1970s. Of interest is the three-story brick structure with a tiny mansard roof and narrow window openings, the first new building to be constructed after the Mile of History was underway, replacing the Jules Patry wholesale warehouse that had left Sussex for the City Centre in 1963. Designed by Rosen, Caruso, Vecsei Architects of Montreal, it was an early effort at historicized modernism which has since been more heavily historicized with a more quaintly ornamented storefront.

Back to the beginning - in conjunction with the NCC's Advisory Committee on History in 1960 the restoration architect Peter John Stokes was retained. Through his elegant restorations at Niagara-on-the-Lake Stokes had established a reputation for historic sensitivity. He was asked to prepare specifications for the restoration of Sussex Street which 'when restored would have all the exterior finish completed in immaculate detail, to resemble the Confederation period. Store signs, windows, doors and awnings would be made to conform to those which were known to have previously existed.' The buildings X'ed out in this street elevation actually refer to later events in another block. (Preserving Our Heritage, NCC 1961)

The concept for a Mile of History was in large part sparked by the destruction of this handsome stone building at Sussex and Bruyere Streets, Thomas Goulden's Hotel (1852-1860). Judged to be one of the finest buildings on the street, its demolition was opposed by the Ottawa Historical Society which appealed to the City of Ottawa to save it, and a personal intervention by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. It was a great loss but it provided the impetus for some form of government action on the Mile of History. (Photo: LAC-e010934805)

Despite these protests, in December 1959 the fight was lost and the demolition proceeded the following summer for a gas station. Nonetheless it had a galvanic effect on the NCC, which had just been given the mandate to administer the conservation and restoration of historic buildings. (Photo: City Archives AN-004606)

Shortly after the ambitious report had been adopted and approved by the Government of Canada and just before the NCC could move to expropriate the buildings, one of Sussex's key blocks was significantly diminished when the Hotel du Canada and the Bishop's Block at the corner of St.Patrick Street were heavily damaged by a fire, and were taken down. (Photo: Michael Newton, Lower Town Ottawa, NCC 1980)

On the other end of the block at Murray Street the Laurendau Block-Valin Apartments met a similar fate, in the same year. By the time that the NCC acquired it the building was a burned shell, and their first action was to demolish it. (Photo: Michael Newton, Lower Town Ottawa, NCC 1980)

This was the St. Patrick-Murray Street block in its entirety although it was misidentified as Murray-to-Clarence in the 1961 report. Cost-recovery for the purchase and restoration would be amortized through office space rentals 'within a surprisingly short period'. It noted that 'Areas in other cities that have been preserved in this fashion have become a mecca for discriminating tenants, and it is not unrealistic to suggest that space in this area might become among the most sought after in Ottawa.' That prophesy has not come to pass, and during the ensuing decades commercial tenanting has been problematic.

Despite the availability of Peter Stokes' drawings and historic photographs, the NCC has not rebuilt the missing ends of the St. Patrick-Murray block, although it has never been hesitant about improving on history. (Photo: Michael Newton, Lower Town Ottawa, NCC 1980)

Five of the buildings on Sussex Drive are now facsimile reproductions of the original ones. This is a practice perfected by the NCC for reasons of efficiency and marketability, a technique that is not entirely embraced by the heritage industry.

Does Facadism always equal Disneyfication? It's the least best option for historic building restoration, but it's too late to ask. The National Capital Commission was proud of its work. (Photo: NCC Annual Reports)

In the four blocks beyond St. Patrick Street (top half of the 1961 report's drawing above) given the presence of three major institutional buildings there was no need to demolish and recreate - with the Notre Dame Church, Academy de la Salle, and the Grey Nuns/Sisters of Charity Convent in safe hands. This left only the Bruyere-to-St. Andrew section of Sussex, the site of Goulden's Hotel, to be dealt with. Which the NCC did with some enthusiasm, as it soon expropriated the gas station property, demolished the building, and built a small parking lot buffered by landscaping. In Peter John Stokes' concept plan this block was suggested for a new office building.

News of the Government of Canada's surprise announcement to expropriate the northern half of Sussex from Cathcart to King Edward was buried by their decision one month later (April 12, 1962) to seize five times as much land on Lebreton Flats. The Sussex expropriation of 32 acres containing 400 households came as 'a bit of a bombshell' during Ontario Municipal Board Hearings into a new medical-dental building proposed for the area. The NCC plan would ease all trace of Mactaggart, Redpath, and Baird Streets, and the former CPR railway yards. This tract of land was to be used for a variety of purposes, including new government buildings, the approaches to the proposed Macdonald Cartier Bridge, redevelopment of the 'Mile of History' running from St. Patrick Street to City Hall, and a further addition to the Rideau River shoreline park. (Ottawa Journal, March 14, 1962)

It was unclear how an extended Mile of History could possibly fit into the plans for a new roadway and government buildings, which required the removal of vast amounts of earth to create the interchange between Sussex and the Macdonald Cartier Bridge. (Ottawa Journal, August 24, 1963)

After all of the historic buildings north of Boteler Street had been cleared away the Mile of History was effectively terminated at the bend in Sussex Drive. (GeoOttawa, 1965)

Any possibility that the Mile of History that might have lead to the gates of Rideau Hall was permanently halted by this beast, the Lester B. Pearson Building, headquarters of the then Department of External Affairs (Webb Zerafa Menkes and Housden Architects, 1969). The architects defended their design as being extremely sensitive to its setting, but the External Affairs building was excoriated for being a hostile bunker. While it's mellowed somewhat with age it's hard to believe that its designers had ever visited the site. (Photos: Ottawa Journal, April 28, 1973, OFART-Old Foreign Affairs Retired Technicians)

By 1965 the Pearson Government's hardened stance on Sussex Drive had softened, a little. In his article ‘Old Street With a New Face’, architect Stig Harvor of Balharrie Helmer Associates summed up the change of heart. ’The austerity program of 1963 shelved plans of converting the building interiors into rentable, modern office space. The only work undertaken to date has been the exterior facelift. But what a visual change this facelift has produced! The buildings have regained, and one suspects, often surpassed, their old charm. They now form the only comprehensive attempt in Ottawa - and perhaps in Canada - to create a ‘streetscape’ where building materials, facades, colors, store fronts and signs are looked upon as a total composition rather than a composite of unrelated parts. We have the example of Sussex Drive as a dramatic illustration of the big effects which can be achieved with small means. Under the expert architectural eye eye of John Leaning, the National Capital Commission has spent about $80,000 to give Sussex Drive a colourful new appearance. - ‘Old Street With a New Face’ by Stig Harvor, Ottawa Journal, May 28, 1965. For about 1% of its original estimated cost the NCC had given the street a cheap and cheerful makeover. (Photo: NCC Annual Report, 1968)

By the early 1970s the Mile of History project was in the ascendancy at the NCC. Work was hastened when one of the commercial buildings between George and York was destroyed by fire. The hole needed to be filled and while they were at it, the little building next door containing the Rose Cafe and La Hacienda could be improved upon. (Photo: City Archives)

It provided the first opportunity to put the NCC's new approach demolishing the existing buildings they deemed to be too 'structurally unsound', build facsimile historic facades attached to modern buildings that would serve another purpose - in this case commercial units at grade and loft apartments above. They would go on to do this to the Castor Hotel, and the Hotel du Canada/Laurendau Block.

Sometimes the buildings could be returned to a more 'appropriate' period. The 1870s facade of the Riel-McDougal blocks had been altered in the early 1900s by a fourth floor addition. (Photo: NCC Annual Report, 1974)

When it came time to rehabilitate the building for flats and new stores the top floor was removed and replaced by a highly conjectural attic story. A hybrid of this methodology was followed in the next block for the adaptive re-use of the Institut Jeanne d'Arc. (Photo: NCC Annual Report, 1980)

This philosophy has been the driving principle to architectural restoration on Sussex Drive since 1961: 'Sussex Street, restored to Confederation days, building facades renovated, advertising signs removed, sidewalk widened, trees planted, building signs lettered in period script.'

The Mile of History was not universally endorsed. At the Ontario Association of Architects’ supper discussion meeting with the theme “What Purpose the Centennial?” OAA Secretary Mike Kohler ‘expressed discontent with the Federal Government’s plan to turn Sussex Drive into a Mile of Living History’ and told the gathering that he would prefer to see a national theatre or auditorium built in Ottawa for the occasion ‘since the architecture to be restored on Sussex Drive is not especially attractive.’ (Ottawa Journal, November 21, 1961) ![]()

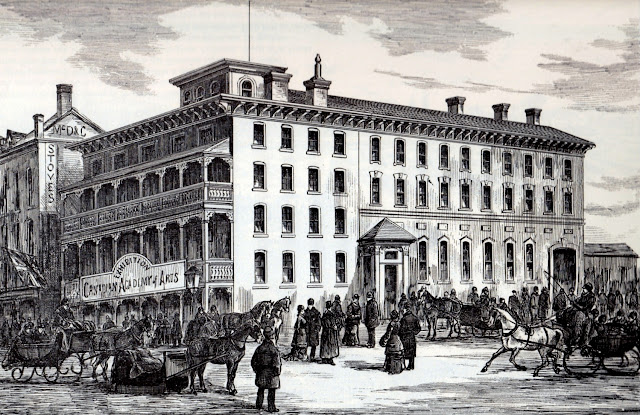

The stone buildings at 541 Sussex Drive were to be the flagship restoration project for the Mile of History. The Ottawa Journal announced the plans on September 16, 1961: ‘Once a fashionable hotel, this building, stripped of its verandahs and with a new roof, still stands on the northeast corner of Sussex Drive and George Street. Today it is used as RCAF Headquarters Dental Clinic. In the year of Confederation, it housed British soldiers here as a guard for the Governor General. Built in 1827 as a tavern, it had a series of names until, in 1875 it became the Clarendon Hotel. In 1880 the Canadian Government acquired the building for the newly formed Geological Survey of Canada, and it was thus employed until recently. Soon it will be restored to its 1867 appearance under the NCC’s “Mile of History” project.’ To this list you could add that it was the scene for the first Royal Canadian Academy exhibition of March 1880, the beginnings of the National Gallery of Canada. (Canadian Illustrated News, 1880) ![]()

Of course its 1867 appearance could not be a target date for restoration, because through its multitude of uses and transformations the building had been rebuilt several times. The history of this building is so complex that it requires a 50-page chronology in Michael Newton's Lower Town Ottawa - Vol 2, NCC 1980- Vol 2, NCC 1980. Michael was an National Capital Commission's in-house historian employed to do the kind of pure research that no federal agency would pay for today. (Photo: LAC a008438)

541 Sussex had been condemned and promised a new life once before, although nothing more came from these plans. ’FOR USE AS A MUSEUM - 'The old Custom House at Sussex and George will not now go under the wrecker’s hammer, Works Minister Winters announced Thursday [December 15, 1955]. Instead it will be turned over to the Historic Sites and Monuments Board for use as a museum.’ (Photo: JRAIC, 1955)

While it was initially the first priority restoration of the building was deferred for decades and it had make do with one of the NCC's interim inexpensive fix-ups, painting stripes on the blind attic story. (Photo: NCC Library)

Its many chimneys are still missing, but a standing seam metal roof, eaves with brackets, and an eyebrow dormer window have finally been returned to the former GGFG Militia Barracks, British/Clarendon Hotel, Geological Survey of Canada, Department of Mines, RCAF Dental Clinic, etc.

Peter Stokes' 1961 plan included an early concept for a chain of landscaped courtyards and parking areas behind the Sussex Street buildings, starting on George Street at the right and flowing through the Murray on the left.

The NCC acquired additional properties at the rear to accomplish this. (Photo: NCC Library)

They were used as surface parking for many years. To hide the lot the National Capital Commission built a stone screening wall with two arched openings along George Street in 1965. I can recall Rolf Latte, the Commission's sharp-tongued Information and Heritage Officer crowing that when the City of Ottawa first established its Heritage Buildings Reference List in 1979 they had been fooled by the NCC's new wall and included it in their list of historic structures.

The wall had to come down for the Clarendon Court.

Through fits and starts the Mile of History has reflected the rise and fall of the National Capital Commission's budgets and political influence. Lauding the plans for the Mile of History in its editorial of June 19, 1961 the Ottawa Journal had said 'It is satisfying the learn that a detailed study has been prepared for part of the street between the Basilica and York Street showing how buildings may be restored, "woven into the historic fabric", to use the NCC's good phrase. ...These plans must not be considered as merely visionary and impractical. The NCC keeps its mind on the main task in bringing forward new ideas. We need more, not fewer plans. We need daring and imaginative concepts which will make Ottawa a city of culture, a place which nourishes humane values, as well as a city of expressways and open spaces.'